Authorship

A Team Effort

Most often the authors of the Heidelberg Catechism are identified as Caspar Olevianus and Zacharias Ursinus. Over the years there has been some scholarly debate about this, especially concerning Olevianus' contribution. Some say that Olevianus, as the pastor, is the one responsible for the direct, warm and personal tone of the Catechism. Others say that Olevianus was less involved. In the end, as with so much historical research, it is hard to obtain definitive answers.

From Elector Frederick III’s preface, though, it is clear that the authorship of the Catechism was a team effort. He writes, “accordingly, with the advice and cooperation of our entire theological faculty in this place, and of all Superintendents and distinguished servants of the Church, we have secured the preparation of a summary course of instruction or catechism of our Christian Religion, according to the word of God, in the German and Latin languages.”

So, at least three different groups of people had a hand in the preparation of the Catechism: theological professors, church superintendents, and church leaders, both ordained pastors and laymen. The last group is somewhat comparable to the consistories or councils that lead many Reformed churches today. The second group needs some explanation. Since the Reformation of the sixteenth century was an ongoing process, some customs and structures from the Roman Catholic way of life still lingered for a time, also in Protestant churches. For example, in the Roman Catholic Church a bishop is a higher-ranking clergyman who has responsibility over a number of priests spread out over a larger area. Likewise, church superintendents supervised the teaching and conduct of a number of pastors in a certain area. Over time the position of church superintendent faded from Reformed church life, but it did not happen over night.

From various sources we have a pretty good idea about who belonged to each of these three groups. The table below summarizes what we know.

|

Theological Faculty |

Church Superintendents |

Church Consistory |

Others |

|

Zacharius Ursinus |

Caspar Olevianus |

Caspar Olevianus |

Thomas Erastus |

|

Immanuel Tremmelius |

Joannes Velvanus |

Adam Neuser |

Elector Frederick III |

|

Petrus Boquinus |

Johannes Willing |

Petrus Macheropoeus |

|

|

|

Johannes Sylvanus |

Tilemann Mumius |

|

|

|

Johannes Eisenmenger |

Johannes Brunner |

|

|

|

|

Michael Diller |

|

It’s impossible from our present vantage point to know how much each person was involved in the overall project. Some would have been involved in writing, others in editing or approving. For the sake of efficiency and consistency, certainly the bulk of the work would have rested on the shoulders of two or three individuals, and Ursinus and Olevianus are the prominent names in the group. Furthermore, the involvement of the Elector himself should not be underestimated. All the evidence indicates that he took a very hands-on approach to this catechism project.

In the end, what matters most is not who wrote which sentence. Rather, we should be grateful that so many different people were involved in the production of the Heidelberg Catechism. This allowed the strengths of everyone involved to be poured into this joint effort, refining and improving the Catechism beyond what could be expected if only one or two people were involved. The clarity, brevity and warmth of the finished project demonstrates that, together, they got the job well done.

Caspar Olevianus (1536-1587)

On August 10, 1536, in the city of Trier, Caspar Olevianus was born. His father, Gerhard, was both a baker and a prominent city councillor. Sadly, he died unexpectedly when Caspar was still young. Caspar was left in the care of his grandfather. After attending the local preparatory schools, his grandfather sent him to France, to study law.

Olevianus proved to be a bright student, but he soon began to learn about more than law in France. He was also exposed to the vigorous Protestant movement, inspired in no small part by the writings of John Calvin. Later, as he was studying law in Bourges, he met the son of Elector Frederick III, who was also studying there. The two became good friends. One evening, though, tragedy struck. The two young men were on a ferry-boat crossing the river. A group of drunken students were also on the boat, causing a ruckus. Before long the boat capsized. Olevianus attempted to save Frederick III’s son. Sadly, he was unsuccessful, though he himself was spared and made it to shore alive. That tragic night had a profound effect on Olevianus, and he vowed to serve the Lord, not as a lawyer, but as a preacher.

Olevianus proved to be a bright student, but he soon began to learn about more than law in France. He was also exposed to the vigorous Protestant movement, inspired in no small part by the writings of John Calvin. Later, as he was studying law in Bourges, he met the son of Elector Frederick III, who was also studying there. The two became good friends. One evening, though, tragedy struck. The two young men were on a ferry-boat crossing the river. A group of drunken students were also on the boat, causing a ruckus. Before long the boat capsized. Olevianus attempted to save Frederick III’s son. Sadly, he was unsuccessful, though he himself was spared and made it to shore alive. That tragic night had a profound effect on Olevianus, and he vowed to serve the Lord, not as a lawyer, but as a preacher.

In order to fulfill this newfound focus in life, Olevianus soon travelled to various Reformed cities, learning from prominent Reformers such as John Calvin, Henry Bullinger, Guillaume Farel and Theodore Beza. It was quite an illustrious group of mentors to have, albeit for a short time. After soaking up as much solid doctrine as he could from these men, Olevianus returned to Trier, his hometown, and began teaching Latin at the local high school in 1559.

However, Olevianus’ passion and vision was to preach the gospel, not just teach some Latin. As he began preaching the evangelical doctrines of salvation by grace through faith, Archbishop Johann von der Leyen made it abundantly clear that he did not appreciate Olevianus’ sermons. In fact, before long, Olevianus and others were imprisoned for their faith. Upon hearing this, Elector Frederick III, and some others, pulled the necessary strings in order to free Olevianus from his confinement and bring him to Heidelberg.

However, Olevianus’ passion and vision was to preach the gospel, not just teach some Latin. As he began preaching the evangelical doctrines of salvation by grace through faith, Archbishop Johann von der Leyen made it abundantly clear that he did not appreciate Olevianus’ sermons. In fact, before long, Olevianus and others were imprisoned for their faith. Upon hearing this, Elector Frederick III, and some others, pulled the necessary strings in order to free Olevianus from his confinement and bring him to Heidelberg.

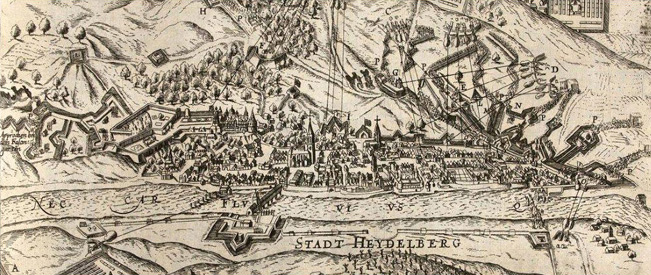

In January 1560 Caspar Olevianus arrived in Heidelberg and began by teaching theology at the University. Soon enough, though, he relinquished this post to Zacharius Ursinus who arrived shortly after he did. Ursinus was better equipped for the responsibilities of a professor of dogmatics. This also allowed Olevianus to fulfill his primary passion: preaching. After a short time as pastor in the St. Peter’s Church, he became one of the preachers in the main church, the Heiliggeistkirche.

Later on, when Frederick III died and Ludwig VI succeeded him as Elector, the circumstances were no longer so favourable for Olevianus in Heidelberg. He was eventually sent out of the city, and went on to continue serving the cause of the Reformation in the area of Wetterau and Herborn. He died in Herborn on March 15, 1587.

Zacharias Ursinus (1534-1583)

Zacharias Ursinus was born on July 18, 1534 in Breslau, along the Oder River, in the area which we now know as Poland. Although his family name in Latin was Ursinus, growing up his friends would have called him by his German name Zacharias Bär. Translated literally, this means Zacharias (the) Bear.

Despite his last name, there is no indication that young Zacharias was a particularly intimidating or aggressive child. On the contrary, he seems to have been quite a quiet and studious lad. He was educated at the local school in Breslau until he was fifteen years old. During that time he probably received some catechism instruction from a certain man named Moibanus. Presumably, the catechism instruction he received in his own youth shaped, to some degree, the catechisms he wrote later on in his life.

Despite his last name, there is no indication that young Zacharias was a particularly intimidating or aggressive child. On the contrary, he seems to have been quite a quiet and studious lad. He was educated at the local school in Breslau until he was fifteen years old. During that time he probably received some catechism instruction from a certain man named Moibanus. Presumably, the catechism instruction he received in his own youth shaped, to some degree, the catechisms he wrote later on in his life.

In 1550, at the age of fifteen, Ursinus moved to Wittenberg and studied under the well-known Reformer, Philip Melanchthon. Some years later he also made a tour of European cities which had embraced the Reformation. Much like Olevianus, on this trip he met leading men of the Reformation, including Henry Bullinger, Peter Martyr Vermigli, and John Calvin. However, by 1558 it was time to return to his hometown of Breslau and begin putting all of his studies to good use. He became a teacher in the local high school and, as part of his curriculum, used the catechism of Melanchthon (Examination of Ordinands 1552) to educate the youth. Whether they always realized and appreciated it or not, the youth in Breslau certainly had a very well equipped teacher to instruct them in the doctrines of salvation.

However, soon enough it became apparent to Ursinus that things were not all well and peaceful in his old hometown. Controversy was simmering, again about the doctrine of the Lord’s Supper. Ursinus, as a student of Melanchthon, tried to take a more balanced and moderate approach to this contentious issue. Not everyone appreciated his stance. Moreover, Ursinus was not the type of man who could endure, let alone enjoy, heated debates for very long. Already in 1560 he left his teaching post in his hometown and travelled to Zürich. After a short stay there, Elector Frederick III asked him to come and teach in Heidelberg. In short order he proved his worth as a theological teacher and was appointed professor of dogmatics at the University of Heidelberg.

During his time in Heidelberg he wrote two other catechisms, his Minor and Major Catechisms, in addition to his involvement in the Heidelberg Catechism. As mentioned earlier, when Ludwig VI succeeded Frederick III as Elector, the political and theological climate in Heidelberg changed. Eventually, in 1578, Ursinus moved to Neustadt an der Weinstrasse and continued to live there until he died in 1583.

——————

Note: further information on the authorship of the Catechism can be found in Bierma, Lyle D. An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology (Grand Rapids, 2005), 49-74.